Biography is one of the oldest art historical approaches. In Renaissance Italy, the 16th-century artist and writer, Giorgio Vasari paved the way for artist biographies when he wrote about some of his artistic contemporaries, including Michelangelo and Leonardo, in The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters and Sculptors. The book helped rocket them into art superstardom and, over 500 years later, it remains a useful source for today’s art historians.

Biography, by helping us to understand the artist, sheds valuable light on artworks. It’s one of the reasons why writing a researched biography of Newt Thomas is an important objective in this project, even if the process of gathering the details is slow and laborious.

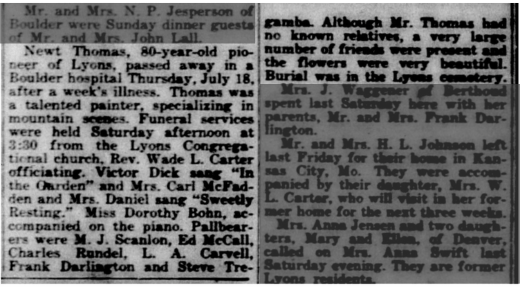

When Newt died in 1940, he was described in the Longmont Times-Call as having many friends but no known family members.

Volume XLVIII, Number 73, July 26, 1940

Surely, he had family. Parents at the very least.

Where was he born? Where did he grow up? What were his parent’s occupations? In what kind of environment did he come of age? Did he like to read? If so, what were his favorite books or stories? Where, or from whom did he learn how to paint?

These are just some of my many questions.

Documents in the Lyons Redstone Museum’s files include basic biographical information drawn from a Lyons Cemetery digitization project, some references to him in family histories, and a few newspaper clippings. Because this type of research is outside my art history training and experience, I sought advice before my spring sabbatical began from Carey Heatherly, University of Montevallo reference librarian and university archivist.

While my scholarly research skills and dogged determination are useful, I haven’t previously done original biographic research and I wanted some pointers. Carey suggested the DIY genealogical website, Ancestry, as a starting point and cautioned me that this kind of research would be time-consuming, addictive, and that, while I should start with a free account, I’d likely end up wanting to upgrade to a paid subscription in order to unlock more resources. He was correct on all counts.

Before long, I’d upgraded Ancestry, and shortly thereafter purchased a subscription to Newspapers.com. While I was finding out more about Newt, I also went down some rabbit holes.

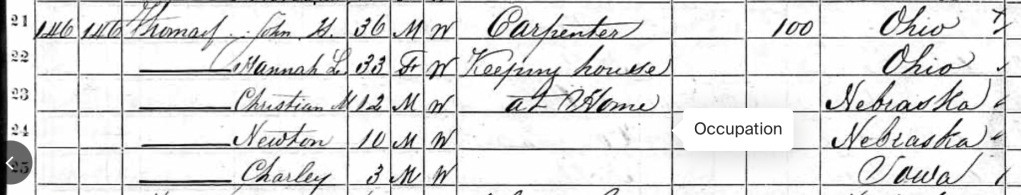

Meeting in the university’s archives, Carey walked me through a preliminary Ancestry search which found Newt recorded in the 1920 and 1940 census as living in Lyons, the latter logged just a few months before his death. He also appears in the 1870 census, when he was 10 years old, living in Pella, Iowa, with his father, John H. Thomas, his mother, Hannah L., and siblings, Christian and Charley.

Ancestry suggested records for John H. Thomas, including military records. Looking at those and others available through the National Park Service, we found that John H. Thomas served during the Civil War, enlisting in the summer of 1861 at the rank of Corporal, serving in the First Nebraska Calvary, rising to the rank of Sergeant, and mustering out in the autumn of 1864.

Carey, who has special interest in Civil War era military history, was excited by the find. The seven year gap between Newt and his younger brother Charley coincided with the dates of John’s service. Carey noted that the rise in rank during John’s service was a mark of good character, that he wasn’t, in Carey’s words, a “ne’er-do-well.” Carey suspected that the Nebraska regiment might have stayed in Nebraska for frontier protection given that the Indian Wars were not over until 1891, and to serve as a reserve force relative to the Civil War. A quick search of the regiment’s history revealed that was not the case, as the regiment had been deployed in expeditions in Missouri, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Mississippi.

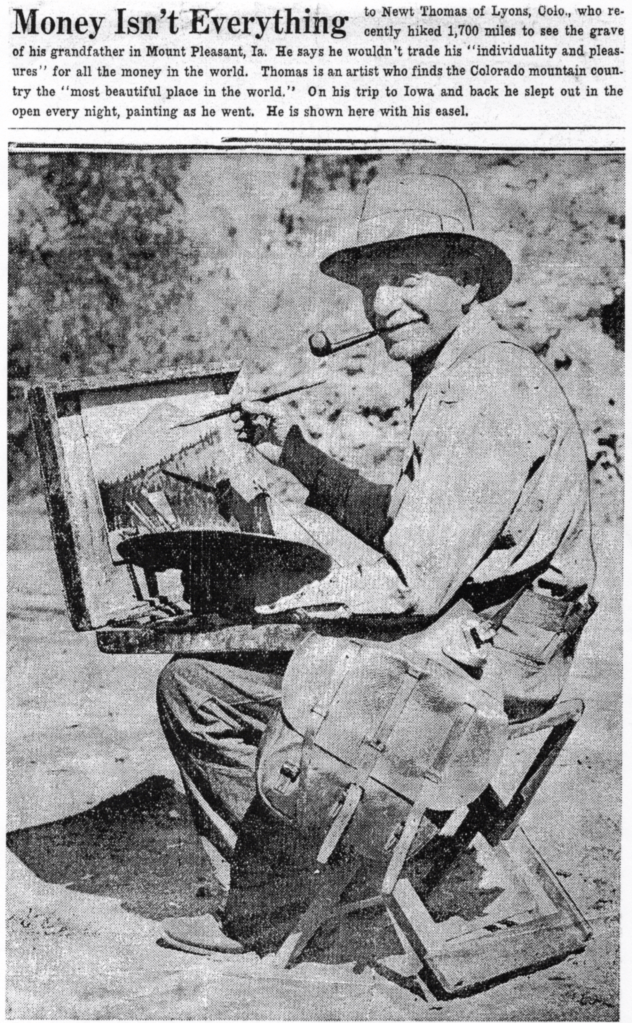

I had been studying the newspaper photograph of Newt painting, visually scouring the photocopied half-tone image for any useful details. Painting a mountain landscape, Newt is seated on a folding stool with an artist’s case in his lap, smiling for the camera with a pipe balanced in his mouth, a paint brush in one hand, and a palette in the other. Cases like the one Newt was using are still manufactured today, they’re especially popular with plein air painters because of how well they function. Basically, it’s a shallow box for transporting paints and surfaces, whether it be paper or boards, like Newt frequently used. When open it serves as an easel. In the photo, Newt’s palette-holding left arm is propped on the bottom edge of the box with his elbow resting on a leather satchel with a long crossbody strap.

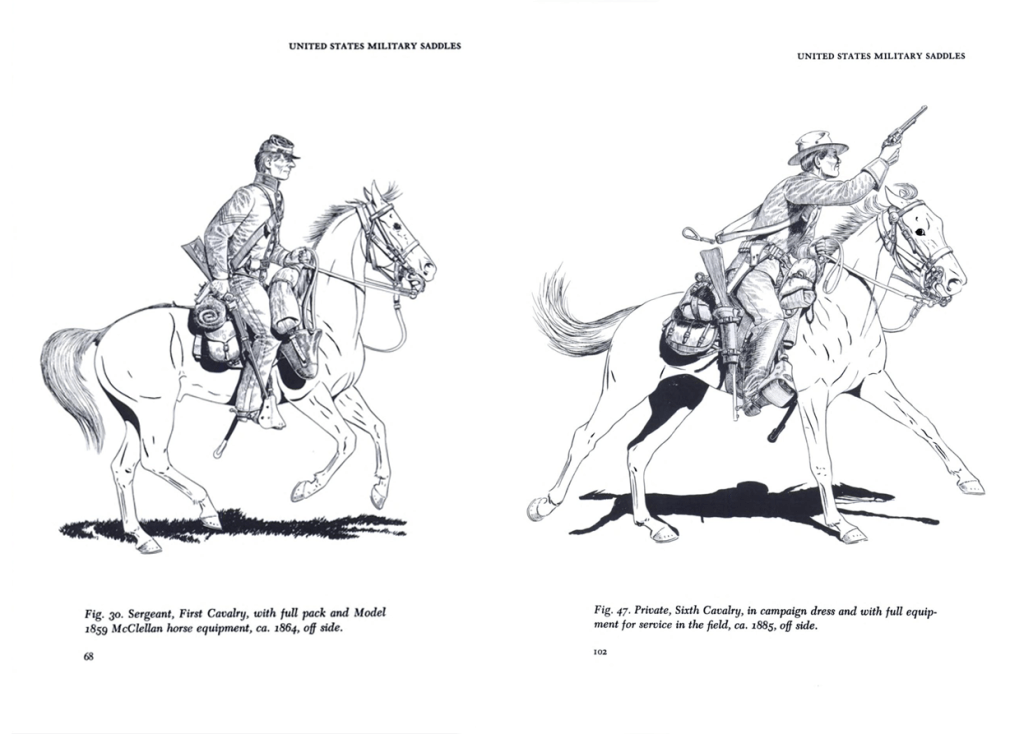

Gazing again at the photo after meeting with Carey and ruminating on our conversation about the Civil War and the U.S. Cavalry, I suddenly realized that the satchel looked like a saddle bag. Using Google, I searched for images of vintage saddle bags and quickly found photos of similar-looking ones attached to famed McClellan saddles used by the U.S. Army Cavalry. I’m familiar with Western tack from having owned horses in my youth, and, while an undergraduate at Colorado State University, I took a hands-on packing and outfitting course that included using a McClellan pack saddle, a variation of the riding saddle. I was surprised I hadn’t made the connection sooner. Many of the saddlebag photos I found online—listings on eBay mostly, military memorabilia sites, and auction houses—were described as Civil War era, leading me to wonder: could the bag have belonged to Newt’s father?

I liked the idea that Newt might have repurposed an object that had once belonged to his father, the Civil War veteran. It wasn’t difficult to imagine Newt having an emotional connection to the bag and, while the romance of this idea was appealing, I knew I had to do more research before I could assert it. And that’s when my hopeful hypothesis fell apart

First, the Civil War saddle bag theory fell apart. After perusing Civil War memorabilia forums and finding Randy Steffen’s useful illustrated book, Military Saddles, 1812-1943, I learned that Civil War era saddle bags, designed to hold horse shoes and a brush, were small and closed with a single strap. The bags available for sale online described as Civil War era that looked like Newt’s large 3-strap bag, I now realized, were mislabeled. Newt’s bag looks like the post-Civil War 1885 model. It was manufactured with slight variations through the turn of the century; the 1904 model was the last one produced and was manufactured in high volume during World War I (1914-1918). After the war, many were surplused and made available in the civilian market. It seems likely that Newt’s hacked saddle bag satchel was made from one of these later 20th century models.

Secondly, I eventually realized I’d been researching the wrong John H. Thomas. The 1860 census records John H., Hannah and their son, Christian living in Pawnee City in Nebraska Territory where Newt and his brother Christian were born. While John Thomas is not an uncommon name, I didn’t consider that there might be two John H. Thomas’ living in mid-19thcentury Pawnee City, Nebraska Territory. The mistake became evident as I began to corroborate biographic data from different sources, comparing census data to Find-a-Grave records.

Find-a-Grave, if you’re not familiar with it, is a useful online resource. It was started in 1995 when the Internet was growing exponentially as the availability of consumer desktop computers and web browsers expanded. Jim Tipton, the website’s found, was a professional website designer who built a website for his hobby of visiting and documenting the graves of famous people. After discovering that other people shared his interest, he opened the website for anyone to create records, which usually consist of the name of the deceased, birth and death dates, a photograph of the headstone, and the location of the cemetery. Most importantly for researchers, the site also includes a good search tool. Ancestry acquired the website about 10 years ago and boasts that it is now the largest site of its type with 238 million records.

A search for John H. Thomas with date and location parameters on Find-a-Grave revealed his burial place in Camas, Washington. The photograph of the headstone noted he had been a Sergeant in Company H of the 1st Nebraska Cavalry. The record also included a list of children’s names: Newt Thomas, Clinton Thomas, and William Patterson Thomas. Clinton and William never appeared in census records relating to Newt, only Charley and Christian. Additionally, John’s wife, Susanna Patterson, not Hannah was buried in the adjacent plot.

Curious to see how a different genealogical tool would construct Newt’s family relationships, I used Family Search, a free genealogical site provided by the Church of Latter Day Saints. There, the pre-populated family tree correctly links Newt to Hannah Coiner but incorrectly to the John H. Thomas married to Susanna Patterson buried in Washington. It was a good reminder that information available on community-based open-source websites is only as reliable as the person entering the data or linking documents, when the person entering the data doesn’t have depth of knowledge or doesn’t cross check, inaccurate information is confounded.

While I might not have connected Newt to a well-documented Civil War veteran, I’ve still been able to build a family tree and cobble together some basic details of Newt’s life that have been helpful in answering questions raised by many paintings in the Portland donation, including…

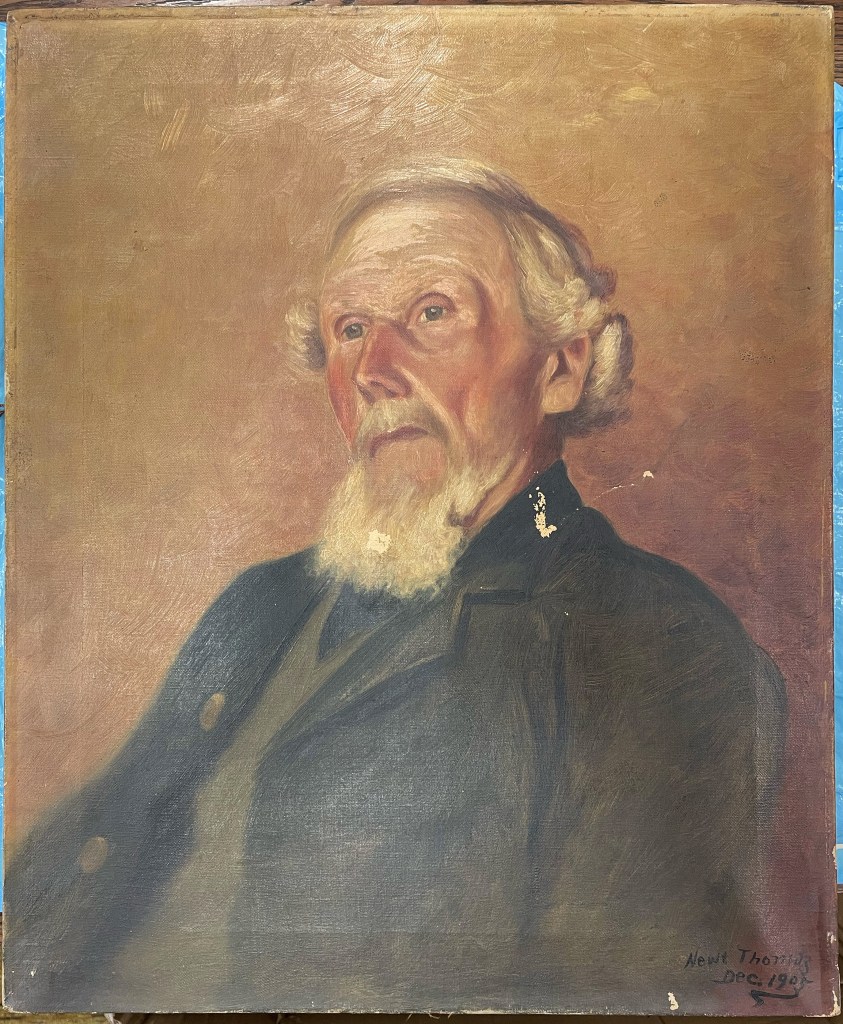

Who is this old man?

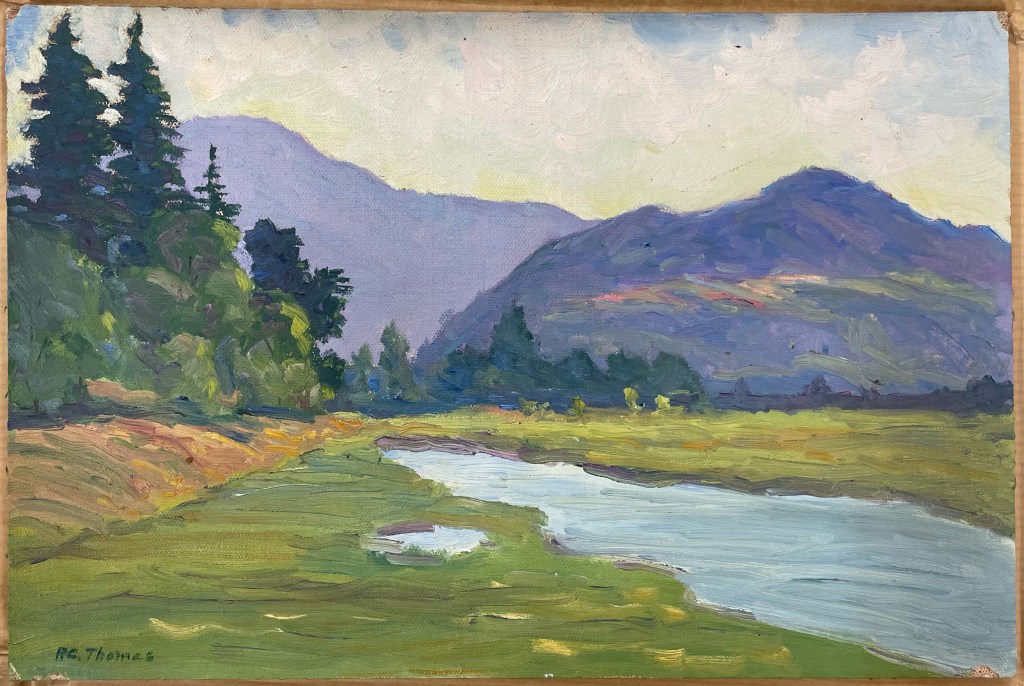

Who is P.C. Thomas?

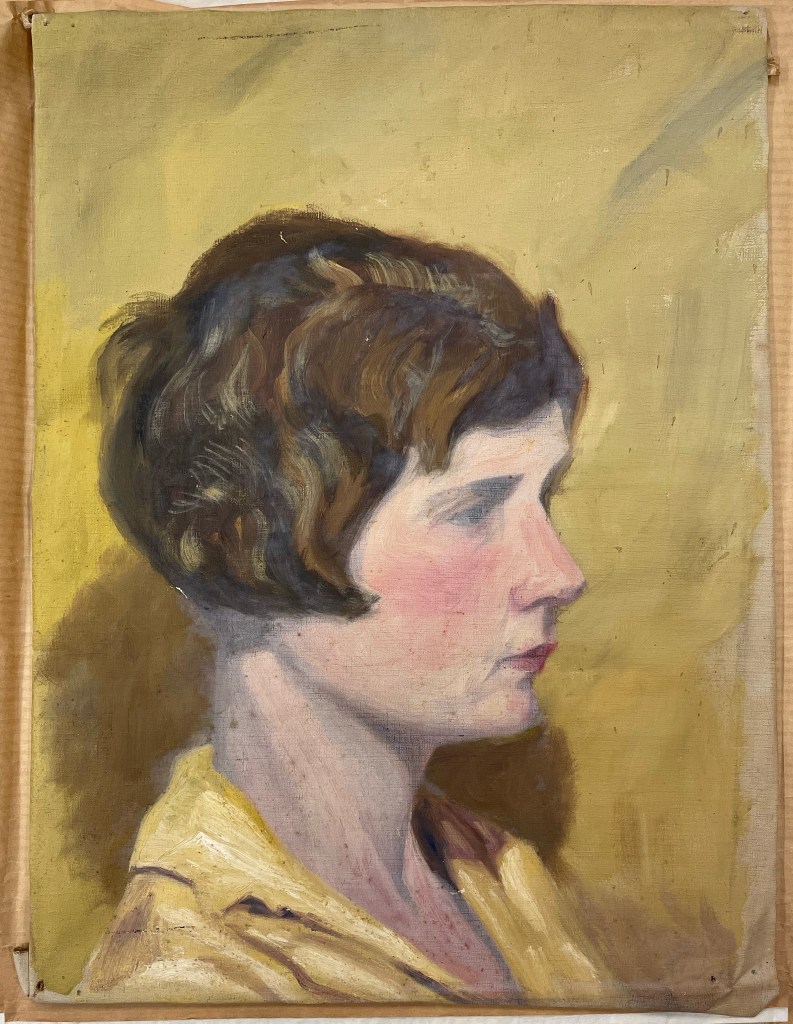

Who is this fashionable young woman?

Whose home is this?

And how does all this relate to Newt?

Find out more in a future post!

One response to “Building a biography”

[…] you read my last post and you’ve been thinking, “I thought she was going to write about the paintings from […]

LikeLike