Until now, the only biography of Newt is found in Denise Berg’s, Piecing a Town Together: Families of Lyons Colorado, published in 2010. It is short and contains some inaccuracies.

Newton Thomas

September 17, 1860-July 18, 1940

Newt Thomas came to Lyons from Indiana. Mr. Thomas had a talent for painting and through the years he could be seen in the vicinity of the town industriously at work on one of his canvasses. he painted portraits, but mainly scenes of the beautiful mountains surrounding the area. One of his favorite scenes was Steamboat Mountain and it was shown in many of his paintings. His work is the prized possession of many of the Lyons family of the early 1900s. In August 1900, he painted a picture of Bryan and one of Stevenson, presidential candidates, for the Longmont Bryan Club. He painted a large sign on the front of the Lyons Mercantile Store, “THE BIG STORE ON THE CORNER.” He also had paintings on the walls of the theatre and on the sign when exiting Lyons.

As of 1901, he had lived in Boulder County for 21 years and never visited Denver. In 1922 his paintings were on exhibition at the Creamery. His works were classed as “equal to any that have been put on canvas.”

Mr. Thomas was a quiet old man and was known to everyone in the region. He enjoyed strolling around the streets visiting with those he met along the way.

Prior to being taken to a hospital in Boulder, he was found in his cabin almost completely paralyzed. He died in the hospital. Services were held at the Congregational church in Lyons on July 13, 1940. At the time of his death he was 80 years old and had been a resident of Lyons for more than 50 years.

What follows here is a more detailed biography that may be expanded or corrected as new information comes to light. Please consider this a work in progress.

Newt Thomas was born in 1860 in Nebraska Territory to John and Hannah Thomas. His place of birth was likely Pawnee City, where his family, including one-year old brother Christian, were recorded as living in the 1860 Census. The Thomas family had previously lived in Iowa, and they may have moved to the frontier city about 200 miles southwest of their home in Des Moines for new opportunities.

John’s skills as a carpenter, his recorded occupation, would have been in demand in the newly-established town. With the indigenous Pawnee population decimated by disease and crop failures (remaining survivors would be forced to relocate to reservations in Oklahoma in 1873), Euro-American and a few free Black settlers were flooding the area, establishing farms in the rolling hills of grasslands and forests west of the Missouri River. Pawnee City, situated on a rise near the confluence of several creeks, had been surveyed in 1857 and incorporated as a town in 1858. Supporting the town’s development, the first businesses established were two sawmills and a general store, carpenters were surely in demand.

Between 1860 and 1870, the Thomas family returned to Iowa, this time to Pella Township, located about forty miles southeast of Des Moines. The 1870 census recorded a new addition to the family, Charley, three years old, born about 1867. Founded in the 1840s by prosperous Dutch farmers seeking relief from religious persecution in The Netherlands, Pella was a growing city when the Thomas family arrived. Like Pawnee City, Pella would have been attractive to a carpenter like John Thomas.

Newt isn’t recorded in the census again until 1920 when he was a 59 year-old bachelor renting a house on Seward Avenue in Lyons. Why Newt went to Colorado is unknown, although the flow of people moving west in search of better opportunities was a general trend at the time. An artist, he may have been drawn there to see the famous Rocky Mountains that became the subject of so many of his paintings. It’s worth noting that seven miles southeast of Lyons was a ferrying point on the St. Vrain River that was platted as Pella Townsite in 1887 and today is known as Pella Crossing. It was founded by settlers from Pella, Iowa, where Newt lived as a child.

While census records dry up after 1870 as a source of information about Newt, newspapers fill the gap. Local newspapers functioned much like contemporary social media with columns dedicated to community reports about individual’s health, travels, guests, and special events.

Starting with the Colorado State Library’s Colorado Historic Newspapers database I found Newt indexed twenty-four times. The earliest reference occurred in the 1890 first edition of the Longs Peak Rustler, a short-lived paper published in Lyons. Most Colorado stories are found in the The Lyons Recorder, with the last mention of him being an obituary in the Longmont Times-Call. Oddly, there is no obituary in The Lyons Recorder. The digitized version of the paper in incomplete and it is possible it has not been preserved.

The brief stories and notes are often just a sentence or two in length. They describe the places where Newt was making paintings around Lyons, including Allenspark, Estes Park, and Camp Angeline, they commend the quality of his “practical work” painting houses and signs, and they report on his frequent travels, often noting when he had been away for extended periods of time.

In January 22, 1914, The Lyons Recorder published a letter from Newt dated January 11 sent from California. After stating he wanted a copy of the paper with his letter published in it to be sent to him, he described his experience in the southern part of the state. He notes that he had been in San Diego and was hopeful he’d enjoy warm weather; however, “Summer in winter time? Nixie, no good for yours truly. I’d rather have the snowdrifts of good, old Colorado than the flower banks of California.”

He considered that he might change his mind when he traveled north, though he didn’t indicate his destination. He also ruminated on seeing the “great Pacific ocean,” seemingly for the first time, and he marveled at the sight and sound of a “flying machine” carrying a man and a woman high in the sky. He warned young men, saying “don’t come here looking for work, but if you come to see the country, all OK. Be sure to have a return ticket or enough money to purchase one.”

The picture of Newt that emerges is of a frequent traveler. On October 21, 1920 The Lyons Recorder reported that Newt was leaving soon for his “usual winter habitation” in Palmer, Nebraska, a farming community about twenty-five miles north of Grand Island. The region then as now is corn and cattle country. He went there repeatedly but always returned to Colorado. In 1921, he was reported as saying, “Nebraska is all right, but give him Boulder County to live in.”

Using this clue I searched historic newspapers using the University of Nebraska, Lincoln and History Nebraska’s web project, Nebraska Newspapers, but the database is less user friendly than Newspapers.com. Searches returned twenty-five results, mostly in The Palmer Journal, with the earliest in 1898, when his return after a three-year absence was announced, and the last in 1938, when he was described as living happily alone in a one-room cabin in Lyons.

Collectively, the Nebraska newspaper provides more details about Newt and they have a different tone than the ones in Colorado. Overall, the articles display fascination with a local man who artistic temperament compelled him to live in the “wilds of the Rocky Mountains.”

Newt’s predilection for traveling long distances on foot is mentioned, whether this mode of travel was forced by necessity, frugality, or preference is unknown.

Sometimes The Palmer Journal spells Newt’s name as Knute, a personal name of German and Scandinavian origin unrelated to Newton. From context in this and other articles, it’s clear that Knute is Newt, thought the reason for the alternate spelling in unknown. Given that the region was settled by many Germans and Scandinavians, the alternate spelling might be typographical error, or perhaps the typesetter was running low on “w” or “e” type and opted for a recognizable phonetic replacement.

He returned to the mountains in midwinter, the day after Christmas, perhaps to paint a sublime snowy landscape. Although Newt is not quoted directly, his voice comes through. It is unbearable for him to stay in Nebraska where his artistic sense cannot be cultivated, the Rocky Mountain wilderness where he finds happiness, is describes in a particular way–the scenery is so beautiful, it approaches the sublime.

The choice of words reveals an artistic eduction. Beauty and the sublime are philosophical concepts that ground 19th-century landscape painting. The popular Hudson River School painters, like their European counterparts, were influenced by philosopher Emmanuel Kant’s essay on the terrible beauty of the sublime and created paintings of majestic landscapes designed to evoke feelings of awe, and potentially fear, of the vast power of nature.

In addition to the red sandstone quarries that made Lyons famous, there were scores of gold, silver, tellurium, and coal mines in Boulder County. Did Newt engage in prospecting? Or was he just bringing back objects he knew people would find interesting?

Two months later, Newt was heading back to the mountains, lured by “the wild beauty” that “is too much for him to resist.”

Occasionally, notes such as this story reposted from The Palmer Journal reveal Newt’s sense of humor and illuminates how he relished his independence.

Studying Newt’s appearances in the newspapers, a pattern emerges. He frequently spent fall to mid-winter in Palmer, where he was described as a former resident, and he was returning for corn husking season when he could make good money in a short amount of time. It’s not far fetched to extrapolate that this seasonal work supported his artistic practice.

Although mechanical corn pickers became available in the 1920s, corn was commonly harvested by hand until after World War II when mechanization of agriculture intensified with the rise of industrialized corporate farming and greater yields per acre rendered obsolete human and horse labor in the fields.

My father, raised on horse-powered farms in northern Colorado, explained the process of husking corn to me: teams of huskers, usually boys and men, walked a field of dry corn with a team of horses hitched to a wagon fitted with tall boards on one side called the bang board.

Husking gloves (more straps than glove) were used to pop the ear from the stalk. After separated from the stalk, the ear was tossed against the bang board so that it dropped into the wagon bed.

My father emphasized how exhausting husking corn was and recalled always tucking his sleeves into the wrist strap to avoid being cut by the jagged edges of corn leaves.

In October 1925, The Palmer Journal reported that Newt had arrived in excellent health for husking corn. By December, when he left after husking 1700 bushels during the season, Newt declared it “too hard for a man his age and he didn’t expect to return.” He was 65 years old.

The newspapers, which regularly reported on people’s health conditions, never mention Newt being sick or injured. In fact, Newt seemed to be quite robust. In 1917, The Palmer Journal said he had “walked practically all the way” from Colorado to Nebraska and, in 1933, they reported that he had recently walked from Colorado to Mount Pleasant, Iowa.

Although he professed to quit husking corn in 1925 he returned to work the fall harvest at least once before 1928. In this year, when he was 69 years old, The Palmer Journal reported that Newt “says that there used to be quite a bit of romance in coming back here in the fall, taking a team and wagon to the field, and watch the corn pile up, but the last few years he says it has been hard work and will not do it anymore.” It’s the last reference to him working husking corn.

This film, shot on a farm in Nebraska in 1931, gives a sense of what Newt experienced.

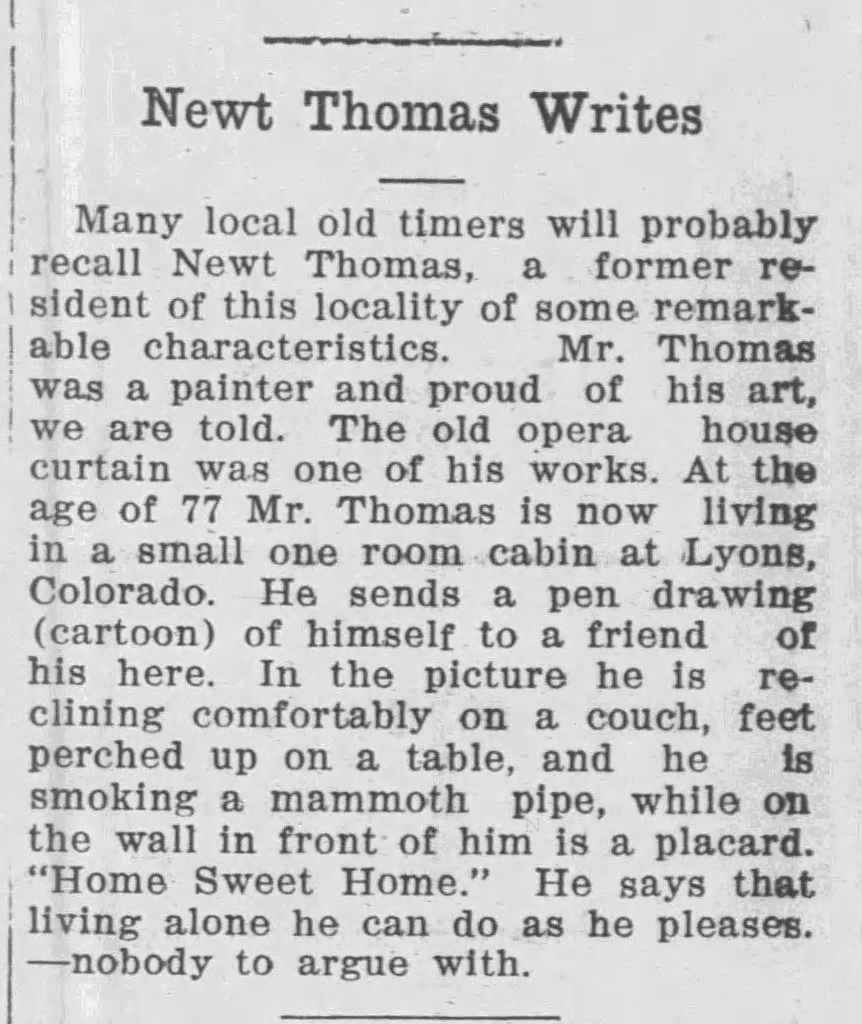

After 1933, aside from an obituary in The Longmont Times-Call and a belated announcement of his death in The Palmer Journal in 1941, Newt appears in a newspaper only once more, in 1938 when The Palmer Journal reported on the receipt of a letter and a drawing from Newt to a friend in Palmer. It seems as if the editor did not know Newt, and his occupation is referred to in the past tense: “Mr. Thomas was a painter and proud of his art, we are told” (emphasis mine).

Reading this, I was intrigued by a painted opera house curtain. It wasn’t unusual for a small farming town like Palmer to have an opera house. Historic American opera houses had little to do with opera performance and were an important part of communities. William Condee succinctly explained how they functioned in the introduction to his book about opera houses in Appalachia:

Opera houses were central to American life from the end of the Civil War through the 1920s. Most towns and cities, from small to large, had at least one opera house. This was the golden age of the opera house, and it is no coincidence that this period was also the golden age of popular entertainment, fraternities, coal mining, and railroads. All these aspects of American life converged in the opera house. Little, if any, opera was actually performed in these buildings. An opera house was a community entertainment and meeting hall.

Using online resources through History Nebraska I searched for the Palmer opera house. While I didn’t find anything specific, I did come across a citation for The History of Palmer: a chronicle of the people from the Indians to the people who settled in and around Palmer, Nebraska, from the early 1800s through the community’s centennial in 1987, a book published in 1989.

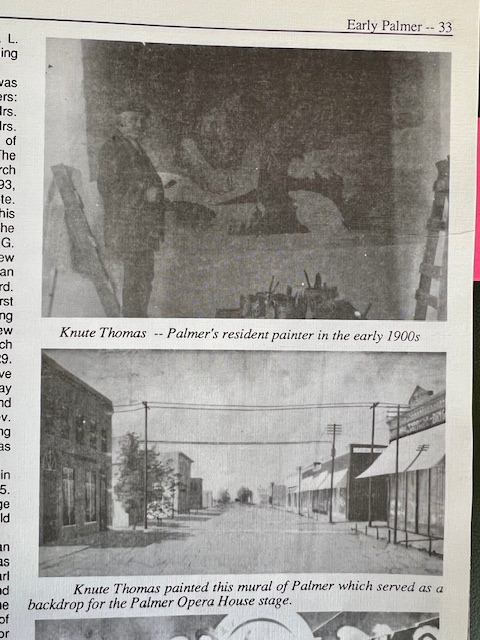

General internet searches turned up the Merrick County History Museum located in Central City, located about 20 miles from Palmer. I contacted the museum, explained the project, and asked if they had any information about Newt. I received a warm reply from the director, Schavon Cordsen, and a copy of a page from the Palmer history book with a photograph of Newt painting and the painted opera house backdrop!

Unfortunately the image of Newt is dark and blurry and the book does’t credit who contributed the photograph. Nonetheless, I have been very excited by this find. The view of downtown Palmer in precise one-point perspective is another indicator of his artistic training. I’m intrigued by the painting behind Newt, is it a landscape? Maybe. Given that all his known paintings are small in scale, I wonder if it was painted for a performance.

Looking closely, I noticed that Newt is wearing a beret. Given that he painted western mountain scenes and that, in the only other photograph of him, he’s wearing a common fedora and a saddle bag satchel draped over his leg, I was surprised to see him looking so bohemian. Bohemian is a term used to describe people in the late 19th- to mid-20th century who rebelled against the status quo, they were often connected to the creative arts.

Modern artists often consciously cultivated a bohemian personal style, such as wearing berets or other casual clothing, because to be bohemian was to be modern and rebellious. Newt, a landscape painter working in the tradition of 19th-century Impressionism, wasn’t avant-garde (meaning pushing the boundaries of artistic convention). However, as a dedicated artist who responded deeply to the aesthetics of natural beauty, he was certainly an outlier in the conservative rural farming communities where he was born, raised, and lived.

As for the opera house, I wondered if it still existed, whether the painted backdrop might still be in it, and if more paintings by Newt existed in Nebraska There are few references in The Palmer Journal of Newt painting the Nebraska landscape, so it is possible.

Finding a Palmer community page on Facebook, I posted the image of the page from the Palmer history book and included a brief explanation of the project explaining that I was looking for any trace of the artist. Within days I’d received replies from two women, Karen and Kelsey, the granddaughters of Mark Lambert, the opera house owner.

Kelsey has been storing the backdrop, which she says was found by her father in the opera house shortly before the neglected building was torn down in 1979 or 1980. She recalls it being displayed in the Palmer High School auditorium during the town’s centennial celebration in 1987, after which it was rolled and wrapped in plastic. She and her sister hope to unroll the painting sometime soon to inspect it (I provided suggestions as to how to do it safely to avoid damaging the painting given its unknown condition).

Additionally, Karen is looking for a small painting by Newt her father says he put in storage. I would be happy to see any painting by Newt, but I am hopeful it is a Nebraska landscape as I would like to see how he painted his home state compared to Colorado. I very much look forward to hearing their report and having the opportunity to see the paintings in person.

If you read my last post and you’ve been thinking, “I thought she was going to write about the paintings from Portland?” Hang tight, I’m getting there and I appreciate your patience.

Now that I’ve established what we know about Newt from census and newspaper records, we can make sense of the “Portland paintings,” a collection of artworks unexpectedly donated to the Lyons Redstone Museum in 2016. Because I’ve yet to uncover records of Newt in or traveling to Oregon, these artworks function as physical rather than textual artifacts that place him there around 1929, and they bring a new dimension to the story of his life.

As it will take some time to explain, the topic of the next post will focus on the detective work I’ve engaged in to identify some of the subjects, both people and places, in this collection of paintings.

I hope you’re enjoying reading about Newt and the research process. Feel free to ask questions! You can contact me here.

Sources

Andreas, A.T. History of the State of Nebraska. “Pawnee County, Part 2.” (Chicago: The Western Historical Company), 1882. http://www.kancoll.org

Berg, Denise. Piecing a Town Together: Families of Lyons Colorado. (Lyons, Colorado: Kumpfenberg Ventures, 2010), 269-270.

Andrew Berman, “How Bohemians Got Their Name,” Village Preservation Blog, April 16, 2013. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2013/04/16/how-bohemians-got-their-name/

“Cornhuskers in Demand,” History Nebraska. https://history.nebraska.gov/cornhuskers-in-demand/

William Faricy Condee, Coal and Culture: Opera Houses in Appalachia. (Ohio University Press, 2005), 3.

Moore, Sam. “Mechanical Pickers Were Off to a Slow Start,” Farm and Dairy, October 26, 2017. https://www.farmanddairy.com/columns/mechanical-corn-pickers-were-off-to-a-slow-start/452704.html

Schabacker, Tim. “Historical Summary of Pella Crossing”,” 2010.

https://bouldercountyopenspace.org/naturalhistory/pdf/pella-history.pdf