While recently visiting my parents in Fort Morgan, in rural northeastern Colorado, I planned a day to drive to Lyons with my mother as my travel partner to meet Monique, the Lyons Redstone Museum Collections Manager, to give her a research update and to check out a few things around town.

The tips of the Rocky Mountain peaks to the West are just barely visible from Fort Morgan on a clear day. The city was once a stop on the Colorado branch of the historic Overland Trail that followed the path of the South Platte River. It’s big sky country dominated by agriculture: corn, wheat, alfalfa, sugar beets, beef and dairy cattle, and related agribusiness.

The South Platte River near Fort Morgan.

My mom, always a great road trip planner, suggested taking a break at Milton’s gas station in Kersey which she recalled as having good grab-and-go breakfast burritos. We confirmed that they were still worth the stop; our hearty and delicious burritos sustained us most of the day.

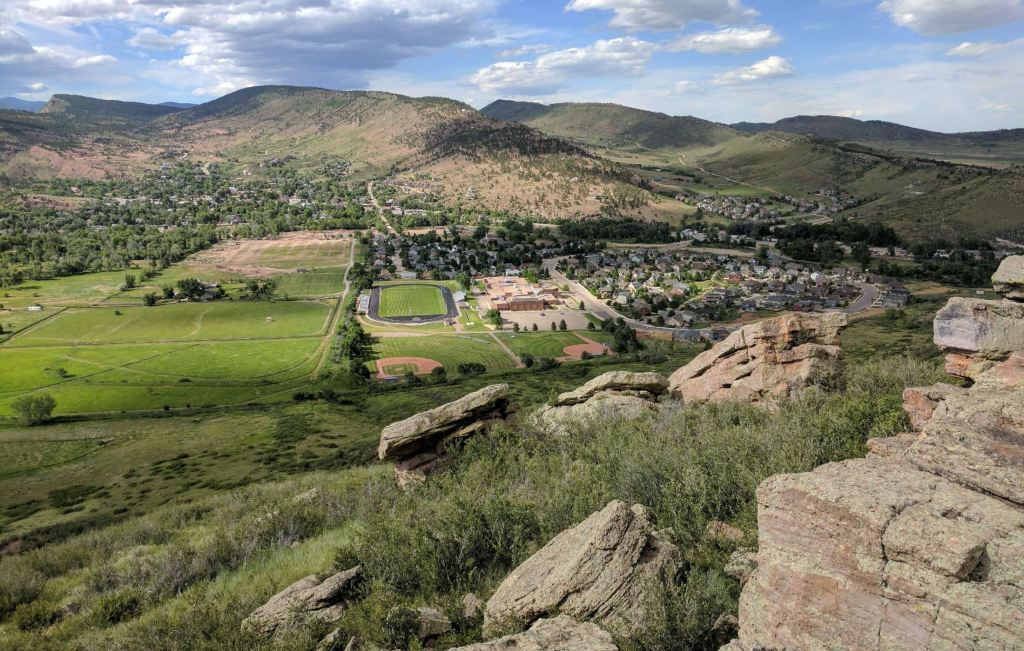

The 90-mile drive from Fort Morgan to Lyons passes through several ecoregions. The High Plains and Rolling Plains, where you might catch a glimpse of antelope grazing in the shortgrass prairie from the car window, change subtly. Entering the Front Range Fans is more obvious, the low hills and more verdant landscape offers expansive views of the mountains. On our trip, we had a spectacular view of the Never Summer Range all the way down to Pike’s Peak. Lyons, tucked into the foothills at the confluence of the North and South branches of St. Vrain Creek, sits in the narrow strip of the Foothill Shrublands, a transitional zone between the Great Plains and the higher-altitude alpine forests.

View of Lyons. Source: https://www.townoflyons.com

More than twenty-five years have passed since I lived in Colorado and the landscape along the Front Range has changed dramatically with urban development replacing countless farms, pastures, and prairie dog towns. These days, I often know where I am on the map, but no longer by sight.

I frequently wonder how, in an increasingly hotter and drier climate, the environment will sustain so many people. Between 1980 and 2020, the state’s population doubled and steady population growth is expected. You don’t have to look at statistics to believe it, you can see it in the massive housing tracts, widened roads, new highways, and commercial developments.

I think a lot about water in a semi-arid environment that has been experiencing a decades-long “megadrought,” the driest period on record over the last 1,200 years. The water in the Denver Basin Aquifer that supplies groundwater to the region is often referred to as “fossil water” because of the length of time it takes to recharge. The percolation process is so slow it’s considered non-renewable and some models even predict it could run dry in as little as fifty years. Until the time when dwindling natural resources force the issue, developers will continue to build for people flocking to the region and loving the environment not only to its detriment, but ultimately their own.

I realize I’ve digressed from telling the story of my most recent research-related visit to Lyons, but these are the things I think about while driving in Colorado. Of course, I also marvel at the beauty of the landscape, relishing views of Longs Peak and Meeker Peak looming behind the Twin Sisters that I’ve known my whole life. They’re my stable point of reference, my North Star.

View of Meeker Peak, Longs Peak, and the Twin Sisters from Highway 66 a few miles east of Lyons.

I was greeted at the museum by Monique who warned me that the old stone building was cold compared to the warm March day outside. She introduced me to the museum’s director and president of the Lyons Historical Society, Jerry Johnson, a tall man whose smile and good-natured laughter reminded me of his mother, LaVern.

We talked about the project and he gently inquired if it was something for which I might expect some kind of payment. I replied with a laugh and said, “No, this is what I do.” I explained that, as an academic working in a public university and on a public art history project, I was working for the public good, not money. (Which is not to say that any support to offset the costs of this project is not gratefully welcomed!)

After saying goodbye to Jerry we sat down with my laptop so I could show Monique my recent discoveries about Newt. As it true with most things I’ve studied, the more I learn the more I realize I don’t know, and so, with Newt, it often feels like I don’t know much about him at all. Monique’s reactions to the results of my research reminded me that I really am fleshing out his life.

Finding Newt in Newspapers

As I’ve been searching historic newspaper databases looking for mentions of Newt, I’ve realized that significant portions of newspapers in the past functioned like today’s social media. Short posts, sometimes just a line or two, tracked what people were doing, where they were traveling, who was sick or recovering from illness, who had out-of-town visitors, and more.

They’re not the sorts of things that we’d consider newsworthy today, but they are what we commonly post in our social media. People in a community want to know about the events in each other’s daily lives and, while some aspects of the past are vastly different from our present, some elements of human behavior don’t change much over time.

Snippets of The Lyons Recorder, which I’ve been accessing through the Colorado Historic Newspapers database, a joint project of the Colorado State Library and History Colorado, mention Newt leaving town for months at a time. Some note travel to Nebraska, including one report that he was going to visit “the tenderfeet,” a term usually meaning an inexperienced person, but in Rocky Mountain parlance, it meant people living on flatland rather than in the mountains. I had wondered where exactly Newt was going and why.

Nebraska Newspapers, a historic database run by the University of Nebraska, was difficult to use, so I purchased a subscription to Newspapers.com. It was worth the price when I found Newt referenced in The Palmer Journal and the Central City Republican Nonpareil, both newspapers serving small farming communities north of Grand Island. Complementing the nineteen references to Newt in historic Colorado newspapers, he is mentioned seventeen times between 1889 and 1939 in Nebraska newspapers.

The earliest newspaper record I can find of Newt is in a short-lived paper, the Allenspark Rustler. Allenspark, a geographic area located between Estes Park and Nederland, was a historic mining and ranching region that has largely given way to outdoor recreation with the scenic 55-mile Peak-To-Peak Highway passing through it.

In the first issue of the paper, December 12, 1890, “Thomas, the artist” was praised for the quality of a recently completed equestrian portrait of Lum Foy, reported as a well-known horse trainer and tournament rider. The painting may have been a sign considering the community was encouraged to view it in its location over Lum’s feed and coal depot. It corresponds with several references in The Lyons Recorder to Newt painting signs for local businesses.

I’ve been searching the Boulder Public Library’s Carnegie Library for Local History database and, while I’ve found some really amazing historic photographs of people and places in Allenspark, I have yet to find anything matching the description of Newt’s painting for Foy.

Newt seems to have had meaningful connections to Palmer, Nebraska over many years. In 1898, The Palmer Journal reported, “Newt Thomas, the wanderer, came in from somewhere on the Monday morning freight. It has been some three years since his visit.”

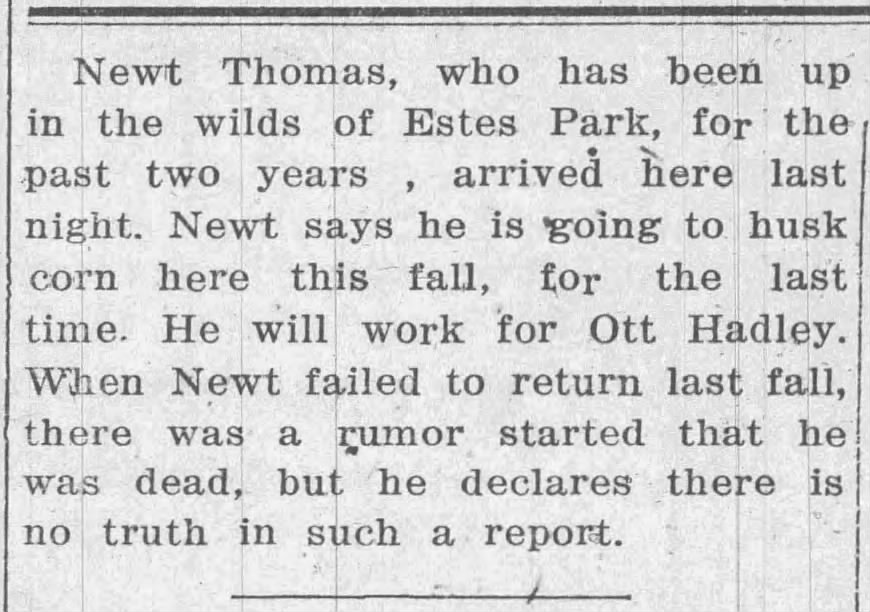

Several later mentions of Newt describe him as a former resident of Palmer and that he returned regularly for the autumn corn husking season. When he didn’t appear for an extended period of time, rumors circulated.

The Palmer Journal, October 18, 1923, page 8.

Two stories mention Newt painting or wanting to paint the Nebraska landscape. Could there be Newt Thomas paintings in Nebraska? I think it’s very likely.

Although these published stories are brief, they help give us a sense of Newt the person. Here are some things they demonstrate:

- Newt experienced a rapidly changing world. In 1914, he asked The Lyons Recorder to publish a letter sent from California, a place that didn’t impress him much though he marveled at seeing Pacific Ocean and a “flying machine” for the first time.

- Newt, like many artists, saw the world differently from non-artists. In 1919, The Palmer Journal explained that “Newt likes Nebraska all right, but the scenery here does not appeal at all to his artistic temperament, and he has to go out and view the wonders of nature occasionally. Through his love of the beautiful, Mr. Thomas enjoys many things that do not appeal to people who are unable to appreciate the artistic.”

- Newt was a good person. In 1920, The Lyons Reporter describes him as a Good Samaritan after he received a bank draft reimbursement from a man who had been robbed while traveling home to Los Angeles. Newt had given the man enough money to purchase his train ticket and meals.

- Newt was a hard worker. Like many artists, he had to support his profession. In 1925, The Palmer Journalnoted that he’d husked 1700 bushels of corn in a season, and reported him as saying that the work was too hard for a man of his age (he would have been about sixty-five years old at the time). Newspaper articles in both Colorado and Nebraska mention him painting signs and houses, a not uncommon supplemental job for artists. Well-known examples include French Romantic Théodore Géricault, who painted a signboard for a blacksmith’s shop in 1814, and the American Pop artist, James Rosenquist, who worked a side hustle as a billboard painter for many years before being able to work full-time as an artist.

- Newt had a sense of humor. A 1920 article, “Hard Hearted Old Bach” in the Greeley Citizen, apparently reposted from The Palmer Journal, reported, “Newt Thomas writes us from Lyons, Colorado, that he is frying his own pancakes and darning his own socks, although surrounded by good looking widows.”

After showing the Nebraska newspaper articles to Monique a warm smile crossed her face.

“We’re getting a clearer picture of Newt as someone who people loved,” she said. “Or at least cared enough to remember.”

An unexpected phone call at the museum

We were interrupted by a phone call from Calvin Schilling, a local Lyons resident. Jerry Johnson, whom I later learned attended high school with Calvin, had called Calvin to tell him I was at the museum.

I knew about the painting because he’d contacted me after I had published an article in The Lyons Recorder last summer. Calvin had called Monique to tell her he was on his way to the museum with the painting and he’d be there in fifteen minutes.

Newton Thomas, View of the North St. Vrain Creek with Cows, n.d. Collection of Calvin Schilling.

Monique was as excited as I was to see the painting in person and it was a pleasure to talk with people equally enthusiastic about Newt. Calvin explained that he’d purchased the painting in 2008 at the O.J. Ramey estate auction in Longmont, a city about 12 miles southeast of Lyons. It was clear that he loves the painting, a winter landscape with cows, and is eager to know more. I deeply appreciate the notes he made in pencil on the back indicating when and where he purchased it.

Calvin also had a copy of the mysterious photo of Newt that came with the Portland donation and a copy of the The Lyons Recorder article written by LaVern Johnson detailing the auction and the life of O.J. Ramey, a Longmont realtor. These important details are the kind of knowledge that so easily disappear and are very important for demonstrating the provenance of artworks.

The style, medium, and materials of the painting—oil on board—are typical of Newt’s body of work. However, other than the landscape with cowboys and cattle on the wall of the McAllister Saloon/MainStage Brewing building, the inclusion of cows in the landscape is unusual, as is the winter scene. The size of the painting, 16×20 inches, is also one of the largest known works. Calvin believes the view is from along the North St. Vrain Creek, on the site of an old stage coach stop.

The stage coach station, formerly the Miller Road House, was a type known as a wayside stop, a place for travelers to rest. It was established by Griffith Evans after being acquitted from having shot and killed the mountain guide and trapper Rocky Mountain Jim Nugent in an argument either over Nugent’s unwelcomed romantic interest in Evan’s young daughter, or their disagreement about the British Earl of Dunraven’s plan to purchase Estes Park (now Rocky Mountain National Park) for a private hunting preserve.

For more about this interesting and twisty story, read “The Lady and the Mountain Man.”

Evans, who had been in favor of Dunraven’s plan, certainly understood that the Lyons location, on a road to the increasingly popular Estes Park, was prime real estate. Evans later expanded the station to include a blacksmith and butcher shop. The property is now owned by Planet Bluegrass, the music event company that organizes the well-known Telluride Bluegrass Festival, and, in Lyons, the Rockygrass and Rocky Mountain Folks music festivals. I have since sent a message to Planet Bluegrass asking permission to look for this view on their property.

While I’m not yet certain about the date of the painting, it does seem to demonstrate Newt in his artistic prime. The color palette is limited and cool, like a seventeenth-century Dutch winter landscape, and the brushstrokes are energetic, including delicate sweeping lines representing windblown snow.

There is an emotional resonance, too. Two cows are depicted, one bawling while nursing a calf, and the other standing still with udders full but no calf in sight.

And is that a cross etched in paint in the rock face above the creek? This painting requires more close looking and thinking.

A promise

A house in Lyons where Newt may, or may not, have lived.

After leaving the museum, we drove past an unusual-looking house where Newt was reported to have lived in a comment posted in a history article in The Lyons Recorder by the property owner.

The owner said he was told by an older resident that the house was built in 1903 as a gift to Newt for painting the pictures in the McAllister Saloon building. While public records confirm that the house was built in 1903, the same year as the paintings were made, the adult Newt doesn’t show up census records until 1920 when he is recorded as renting a house on a different street. It’s not impossible that he lived there, but the story has a whiff of an embellished tale. I’ve written to the property owner, but have not yet received a reply.

While gazing at the house, I couldn’t help but fantasize about finding a trace of the artist in the house, maybe under some paneling or in the attic. The house’s red sandstone foundation has windows, indicating a basement. Perhaps something is hiding downstairs in the dark. More realistically, given that the house, located two blocks from the North St. Vrain, survived the catastrophic flood of 2013, the chance of finding any traces of Newt, if he actually lived there at all, are small. They could have been swept away in the flood or destroyed in a post-flood restoration.

Enjoying the mild late-winter day, Mom and I drove up the canyon on Highway 36 passing Planet Bluegrass and looped back to Lyons on Apple Valley Road, winding through a picturesque area where Newt had probably been painting. Although not over developed, it is now dotted with million-dollar homes in between the historic ones. My mom pointed out the place where her parents used to buy apples from the orchard that gave name to the road. Very few apple trees remain there now, whether that’s the result of development, the flood, or climate change, I don’t know.

Before leaving town, we made a final stop at the Lyons Cemetery where Newt is buried, although his burial plot number was not recorded.

Entrance to the Lyons Cemetery.

Monique says his grave is likely unmarked and I’d like to walk the cemetery when I return, just in case he’s been overlooked. Viewing the cemetery from top of the hill I was surprised by the welling emotion I felt as I thought about Newt being near but still unknown.

“I’m going to find you, Newt,” I said softly, making a promise I hope I can keep.

View of the Lyons Cemetery.

Correction (3/26/2024)

Longmont was described as northeast of Lyons. Longmont is southeast of Lyons. The post has been corrected.

Would you like to receive new posts in email?

Share your address below. I won’t spam you, and I never share or sell email addresses.